1st December

1st December

Thierry Sempere's View on the Andes Geology

At the next edition of the International Congress of Prospectors and Explorers - proEXPLO 2021 - Thierry Sempere will give a talk on "Exploring Peru in search of metals and hydrocarbons using innovative thinking".

In your view, what are the main existing paradigms that are preventing geologists to get the Andean geology right?

Maybe one first point to stress is that there is a sort of “crypto-paradigm” which suggests implicitly that the Andes form one geological entity. In fact “the Andes” are far from being homogeneous, either along or across strike. My opinion is that no generalization should be attempted at the scale of the entire Andes, i.e. from Venezuela to Tierra del Fuego, because it’s always better to avoid comparing apples and oranges.

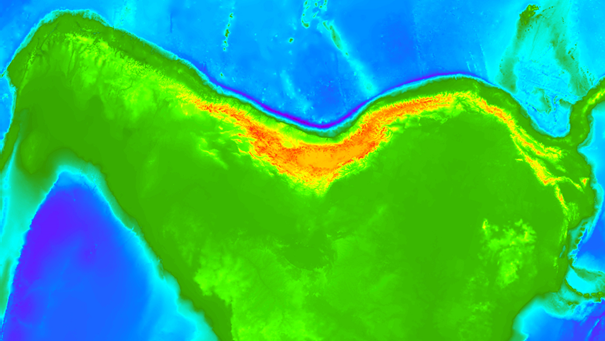

This topographic image of South America and adjacent regions (ocean waters have been removed) clearly shows how variable the Andes are along strike:

This marked lateral topographic variation reflects that the processes – I insist on the plural – that resulted in building the Andes have also varied along strike – and probably across strike, too. We should always remember that. Because my geological experience is almost limited to the Andes and Subandes of Peru and Bolivia, in the following I express myself only on the geology of these countries.

When I say – colloquially – that it is needed to “get the geology right”, I mainly think about the geology dealt with during mining or hydrocarbon exploration: I mean that I’m not talking from an academic perspective. Andean academic geology often tends to be dogmatic and thus to overlook data that fly in the face of preferred paradigms (a shortcoming commonly observed, indeed – see below), whereas exploration geologists, in order to find a deposit, absolutely need to “get the geology right”, i.e. to know what is really down there, whatever the paradigms are.

In my opinion, the main problematic paradigm is the widespread belief that the Andes result only from tectonic shortening imposed by the subduction of the Nazca plate. This belief is now so rooted by tradition that it has turned into a dogma.

As nearly all mountain ranges on Earth, the Andes exist because their crust has been thickened. The current paradigm states that this thickening was achieved by tectonic shortening alone (or nearly so) and rejects the idea that thickening was locally achieved by magmatic additions and/or lower crustal ductile flow, even in part. This dogma ignores that, in a number of regions, the crust is extremely thick and yet no (or very little) shortening is observed. In southern Peru, this key situation has been described as early as 1971 and 1989 by geophysicists, who observed that crustal thickness is maximum along the Western Cordillera (which coincides with the main magmatic arc) and logically concluded that crustal thickening there must have been achieved through magmatic additions along the arc. But these geophysical data and structural observations have been deliberately ignored by the dogmatic geoschools so far. About two decades ago, at a time when I still had faith in the dominant paradigm, I was surprised to observe that, although southern Peru is characterized by a thick crust, this region has been only affected by extensional and/or gravitational tectonics since the Late Paleozoic, confirming the original deductions of the mentioned geophysical works.

Regarding Peru, I’d thus say that this “shortening-only” paradigm has done and is doing a lot of harm, which is reflected in the mapping of almost any fault as a thrust or reverse fault – many times regardless of its evident offset! –, and thus in the production of partly wrong geological maps. The situation is not the same regarding Bolivia, where regional shortening has indeed entirely structured the Eastern Cordillera and Subandes (but, according to my current understanding, the situation in the Altiplano is quite different).

The still common reference to “compressional tectonic phases” in the Central Andes is another major problem. These “tectonic phases” are nothing else that the application to the geology of Peru, by Gustav Steinmann (1929), of Stille’s (1924) concepts – which are now completely obsolete as they were designed for an Earth where continents could not move! But at that time Stille’s ideas had met so much success that within a few years they had become a fashionable landmark in international geology. One then understands that when Steinmann interpreted unconformities he had observed in Peru as compressional “tectonic phases”, he was merely adapting to Peruvian geology this then fashionable interpretive framework. Stille’s “tectonic phases” were meant to explain why “geosynclines” separated by oceans would deform synchroneously in spite of the huge distances that separated them… The fact that the concept of “tectonic phases” was deeply related to that of “geosynclines” suggests that the former should be considered as an obsolete geomyth just like the latter. “Tectonic phases” are nevertheless still massively used as a major interpretive tool in Andean geology – to my bewilderment. It is really a pity that we’re still dealing with the consequences of a groundless geological craze that is nearly one century old.

Getting rid of the “tectonic phase” paradigm should however be easy if one remembers (1) that “tectonic phases” are only interpretations, (2) that these interpretations are now obsolete, and (3) that we should return in each case to the observations that once sustained them. These observations are generally angular unconformities, and each one should be reassessed and re-interpreted using the much richer interpretive tools that are currently available to us.

This point leads me to underline another major shortcoming common in Andean geology, namely the often intricate mixing of observations and interpretations. Although a firm scientific principle is that mixing facts and interpretations should be avoided at all time, this is unfortunately done frequently and tolerantly – especially among the dogmatic geoschools. Whether blatant or subtle, these mixings result in pseudo-scientific “soups” that have misleading meanings.

In order to “get the geology right”, Andean geologists first need to identify and carefully distinguish what are the undisputable observations and data that are available, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, what are the interpretations that have been given so far on the basis of these facts. The observations and data almost never change (if they are reliable), but the interpretations may be completely revised when needed and justified.

Can you comment what Peruvian institutions, universities and companies have done well and not so well in the past to properly understand the Andean geology?

This is a difficult question. I believe most people do generally the best they can, and also that nobody is really in a position to judge them – except maybe historians, but I am not even sure about this. Progress is often messy but is achieved after all, in spite of whatever shortcomings and drawbacks there may be in between.

Your question also opens toward many topics, so many that I can’t deal with all of them here. Therefore I will only address a few.

I would say first that institutions, universities and companies have generally distinct, specific objectives of their own (and their staff also have). In a number of cases, “properly understanding the Andean geology”, as you put it, is not one of them. This does not involve any particular criticism, as it is generally quite understandable – especially in the environments where bureaucracy and/or a bureaucratic mentality have grown out of proportion.

Concerning mineral exploration, one knows of course that discovering a new deposit results neither from a bureaucratic trámite nor the mastery of human relationships, but from a logical processing of variegated geologic information (and also luck!).

But my main answer to your question is that we are all subject to cognitive biases, which are very many indeed (just consult this link and you’ll be amazed). However most of us generally do not realize they fall victim to cognitive biases, unless they have become familiar with the notion. Because they are more experienced, some older persons are less affected than younger people, who are invariably prone to cognitive biases. This is why I’d suggest tthat we should analyse the history of geological knowledge in the Peruvian Andes in terms of cognitive biases, because most shortcomings are rooted in them.

One of these is an excessive respect for tradition. Many Andean geologists seem to believe that the first Andean geologists, from South America or other continents, “got it right” from the start. I am convinced that this is extremely unlikely – how could have they achieved that at a time when geological concepts were so mistaken? – and therefore I only respect their objective descriptions, which in most cases are excellent.

This excessive respect for traditional interpretations explains why obsolete concepts have survived until today (and, I anticipate, will do for some longer time). Because most of them are engineers, it is also a tradition among Andean geologists to favor the blind use of techniques over that of logical or critical thinking. This situation results in a very limited questioning of traditional interpretations.

There are other significant biases of sociological nature. A major bias lies in the unconscious belief that academics who have achieved a high social status hold the geological truth about “the Andes” and are somehow infallible, even over regions they have never studied. It is revealing that a number of companies hire as consultants on the geology of Peru high-status persons who have visited Peru on only a few opportunities, but who are viewed as eminent specialists on “the Andes” in general. The belief that “getting the geology right” is correlated to social status is one of the most amusing I know. One may remember here that those who achieve high academic status are generally dogmatics – and what is most needed for successful exploration are creative people – just the opposite.

This mentality is also reflected in the rather common belief that a person who obtains a doctorate magically converts into a sort of infallible oracle. Indeed, a doctor in geology is often deemed to know almost everything relevant, and to be right on whatever topic, even outside the field of his PhD dissertation, even against the arguments, correct as they may be, of whoever has not obtained a doctorate. In such cases, it is obvious that what counts is the status artificially implied by the doctorate, and not the scientific reality or arguments – and this is much a pity. Of course, this belief that “doctors can’t be wrong” is deeply … wrong. Doctors may well be wrong, just as anybody else.

The same mentality appears in the also frequent belief that any interpretation published in an indexed journal must be right – which is also wrong, of course. It should be self-evident that publishing in an indexed journal does not guarantee – at all – that what is published is the truth!

A similar bias lies in the excessive trust granted to interpretations brought forth by foreigners (especially those from North America or Western Europe) – just because they are or were foreigners. One terrible case is the completely wrong stratigraphy published by Newell in 1949 for the region northwest of Lake Titicaca. This geologist defined his stratigraphy along a section that is in fact cut by a thrust, but did not notice this thrust, and, most surprisingly, did not realize that the succession was repeating itself… This has resulted in a crazy stratigraphy plaguing all geological maps published by the INGEMMET in the concerned region. Twenty years ago, I published in Peru a paper pointing out the error and correcting the stratigraphy, but this has apparently had little effects.

Furthermore, there may be in this case “a bias in the bias”, in the sense that foreign scientists are themselves submitted to sociological biases of their own. Among these are those that induce them to publish papers in agreement with the paradigms favored in their own research system, in order to achieve promotion by their peers. This results in a deeply vicious circle, in which the true geology of Peru or Bolivia may end up being irrelevant to them, i.e. just instrumental to achieve a career. Because I have been myself a foreign researcher on the Central Andes during 34 years, I have had a front-row seat to watch how my (mainly French) colleagues proceeded in order to advance their individual careers, sometimes at the very expense of the scientific facts. For instance, 8 years ago, a young French researcher naively explained to me what conclusions he was going to reach in the Peruvian study that he had not even started to do! – and of course these in-advance conclusions amounted to confirming a paradigm currently fashionable in France… Sociological biases of this sort are just terrible, as they result in the international publication of flawed, if not wrong, interpretations, which may later receive excessive attention in the concerned countries.

These biases converge to give the impression that creativity, as opposed to tradition and dogmatism, may be undervalued in many local contexts. Not long ago, a major and insightful Peruvian geologist wished “more creativity and less bureaucracy” to our community, quite rightly I believe.

My teaching experience over several decades has confirmed this diagnosis. I remember one particular case in which a professor had recommended two “very good” students to me, whom I took later to a field test. They were absolutely unable to analyse by themselves the first simple outcrop I showed to them; they did not even look at the outcrop, and even less see the exposed unconformity, but kept searching in their memory to which units the strata might belong, instead of observing the simple exposure and deducing a conclusion… Thanks to this experience, I clearly understood that teaching may end up being dominantly memoristic, and that in this case the students deemed “best” may end up being those who can repeat exactly the teacher’s words… But favoring memoristic repetition obviously kills creativity. Teaching by favoring memory over logics cannot train students into the experience of logical deductions and critical assessments.

We haven´t seen too much discussion around salt-tectonics in ProEXPLO, do you think this subject is restricted to the “hydrocarbon geologists” or also apply to exploration and mining geologists? How?

I gave a talk in ProEXPLO 2019 on the interest of salt and salt-tectonics for mineral exploration, but I was indeed aware that it might be perceived as a little off-topic by part of the audience. Of course, the fact that a giant salt basin once extended over a large part of Peru (and southwestern Bolivia) should be of the highest interest for hydrocarbon exploration. But it is also interesting for mineral exploration from a number of perspectives: these include the variety of specific structures generated by salt tectonics (which may trap deposits), the high dissolvability of salt (in particular when mineralizing fluids circulate), and of course the capacity of the chloride ion to form coordination complexes able to transport metal ions in solutions. For example, my current research on the Peruvian salt issue is suggesting that specific stratigraphic positions are more prone to host certain mineral deposits – depending on the regional context, of course.

Exploration geologists interested by this issue may refer for details to the mentioned extended abstract in ProExplo 2019 and to the related presentation, which I suppose is also available.

What are the greatest question about the Andean geology that you haven´t found an answer yet?

Another difficult question, and maybe even a perilous one! Most dogmatic geoschools about the Andes express themselves as though these have found all the answers – or nearly so. As I try to keep away from any form of dogmatism, it’s not easy for me to reply.

One point I wish to underscore here is that, in my opinion, much of the progresses achieved during the last 10–15 years have resulted from zircon U-Pb geochronology, because it has provided reliable crystallization ages on a variety of magmatic rocks, and also maximum ages for a number of stratigraphic units (the University of Geneva has been particularly instrumental in achieving this). This enhanced flow of reliable chronological data has allowed to realize what synchronies there may have been between past magmatic, sedimentary, and tectonic processes, and has thus stimulated much thinking about the possible common causes of such synchronous phenomena. This has led to trails and leads, and in some cases to answers. For example, it has appeared that the rapid transition from marine to continental environments observed in Andean Peru at about 90–85 Ma, for which Steimann had imagined the “Peruvian tectonic phase”, was in fact synchronous with the rapid magmatic growth of the Coastal Batholith; this continentalization of the backarc basin thus did not result from a “tectonic phase”, but from the accelerated magmatic growth of the coeval arc! – driving another nail into the coffin of the “Andean tectonic phases”.

To focus on your question, I’d say that in 2017, at the end of my career as an academic researcher, I had come to admit that our knowledge about the Andes of Peru and Bolivia (the Andean segment I have studied) is still rather limited. We are in dire need of many more zircon U-Pb ages, and we are lacking crucial high-resolution geophysical images of the Andean crust and mantle. We also need geological maps that are not biased by preconceptions and paradigms, whether active or not, etc., etc.

I have however to admit that, after nearly 4 decades of studying this Andean segment, I think I have found what I believe are trails toward anwers to a number of questions, especially regarding Peru – but I am not fully convinced that, in the details, they are the correct tracks or leads. I find it characteristic enough that I am continuously improving these tentative answers as new data are obtained and my research progresses (as a matter of fact, I still do research as a consultant).

I tend to view our research activities as multidimensional helixes that spiral around a central point that represents the truth – a point that is in fact never reached, because it will always be impossible to reconstruct in all details the processes that have developed in the past and resulted in building the Andes and generating their ore and hydrocarbon deposits. Of course nobody has reached the truth yet (and even less the dogmatics who think they have), but it is important to remember that nobody will ever reach it either in all details.

From an academic point of view, I currently tend to think that one very interesting and still open question concerns the initiation of subduction along the now Andean margin. Current reconstructions favor that Peru stood in the midst of a major continental collision around ~1000 Ma. One of the involved continental blocks was apparently Laurasia, which therefore must have subsequently separated from proto-South America and moved away, resulting in the opening of an Atlantic-type ocean. This implies that the Peruvian margin must have been a passive, i.e. Atlantic-type, margin during quite some time, and then must have switched to the current active, i.e. Pacific-type, margin at some later time. When did these events occur, and how? What are the geological features in the Central Andes that allow to confirm this narrative? Can we reconstruct details of this initiation of subduction beneath Peru? And what were the consequences of this change for present-day economic geology and exploration?

From an economic-geology perspective, I must confess I have entered too recently the manifold discipline of ore geology to understand satisfactorily the links there must be between the formation of local deposits and the regional evolution. I have initiated a personal research about this captivating issue, but here also I have to confess that my current understanding is preliminary.

Of course the links between mining and regional geologies depend largely on the types of deposits that are considered, and it would be too long to review them here, even in a simplified way. Epithermal deposits in Peru, however, are closely related to young volcanic systems, and I do not think any Andean paradigm change should have a significant bearing on the corresponding exploration – except maybe the fact that extensional tectonics was in fact widespread and might have had some influence on the intensity of fluid circulations among volcanic systems.